Finally reopened after several long months of reconstruction, Mito’s historically rich Kobuntei could be considered the jewel in the crown of the city’s famous Kairakuen. With its delicately painted wall-screens and stunning views of the surrounding countryside, this former aristocratic villa offers a glimpse at a different lifestyle.

Built around the same time as the park itself, Kobuntei was originally used by Lord Noriaki Tokugawa as a home away from home; he would relax and enjoy the beauty of the seasons, entertain guests and grant audiences to his subjects, and keep himself and his forces in readiness for any potential attack from outside.

Constructed with a semi-detached wing just for his wife, concubines, and their ladies-in-waiting, the compound itself is not very large. In traditional Japanese style the rooms are on the inside while a walkway runs along the edge of the house like a veranda, looking out alternately into the well-kept garden or the vista comprising Lake Senba and its surrounds. Though it was burned to the ground during the American air-raid on Mito during the second world war, it was rebuilt shortly after and most of the original buildings and features survive. Some damage from the recent Eastern Japan Earthquake led to it being closed for almost a year to remodel and repair, and now it is an interesting combination of ancient architecture and modern materials.

The largest attraction of the villa is the beautiful wall-screens in the women’s quarters, designed and hand-painted by a celebrated artist from Tokyo’s Arts University. Each room has a different theme to go with its name, covering peach, plum, and cherry blossoms as well as the beautiful red fall leaves. Though painted in a traditional style, some slight elements of the color choice and composition hint at a more modern hand. Lit by the glow of small floor lanterns, the overall aesthetic gives a very nostalgic feel and seems almost inviting.

The women’s quarters themselves are separated from the rest of the house by a narrow hallway, to prevent unsanctioned mixing of the sexes, and face mainly onto the inner gardens. Meanwhile, the men’s quarters occupy the central and upper floors of the house, and gaze out over the hillside and surrounds. The men’s quarters also have some of the interesting technological additions developed as part of Lord Noriaki’s preparations for attack.

Carefully built bamboo blinds on the side of the walkway to the Lord’s rooms allow those inside to see all comers, while being visually impenetrable from the outside. The walkway itself was also built very narrowly, to prevent the traditional Samurai longsword from being drawn inside. The stairs to the upper level where the Lord would spend the bulk of his time are extremely steep and narrow, taking most of one’s concentration just to maintain balance; this was to prevent rival warriors from battling their way upstairs by giving an even larger advantage to those on the high ground. On the landing between the two flights of stairs is a small resting place for warriors to keep watch and prevent insurgence, and the right wall panel of the bottom flight is actually a hidden room from which a Samurai could attack potential invaders from the side as they attempted to head up. According to legend, Lord Noriaki’s fondness for the number 11 led to both flights of stairs having exactly 11 steps; this is because there are 11 strokes in the characters for bushi, or warrior.

There are other novel features on the upper level, such as a rounded door frame made from the remnants left from the making of a giant taiko drum, and a dumbwaiter – type pulley system going directly from the kitchen below into the tea preparation room beside the main sitting room. This of course, was also intended to serve a double-use; in the event of the upstairs being overrun by opponents, the Lord could use the pulley shaft and ropes to slip out via the kitchen and escape.

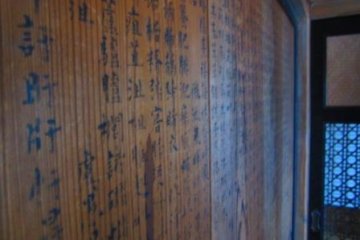

Directly below the upper levels is a large, open space that was designated as the artists’ room. Here poets, artists, and musicians would gaze out on the seasons through the openings left when the removable walls were down, practicing their craft. One of the back walls is actually a kind of kanji dictionary, providing a listing of obscure and hard-to-write characters so that poets could copy them down when inspiration hit.

Beyond just being a historical artifact, Kobuntei offers much to the imagination in describing what life and times might have been like during the final years of the Edo period of Japan. Not only that, but the tricks and traps built-in make it much more than just a lovely view.