Ryozen Kannon, Ryozen Gokoku, and Ryozen Rekishikan, situated close to each other, form like a circle of sadness.

Ryozen Kannon is a memorial to the dead of World War Two, inclusive of all races, as well as unborn babes. Ryozen Gokuku houses and honours the souls of Japan’s war dead, with a special dedication to the martyrs of the Meiji Restoration. Ryozen Rekishikan which I skipped is the museum that details the life and deaths of the martyrs.

The 80 feet high pale stone sculpture of the Goddess Kannon at Ryozen Kannon symbolizes the eternal need for peace with reminders of war and loss its dominant, visible, theme.

The most moving parts of my visit were found in the Memorial Halls. One has an altar containing soil from every cemetery of countries that fought in World War Two. Another contains files of the names of the dead, and worse, missing in action.

The Chapel has letters from ex-prisoners of war commending this place. At the back of Kannon there is also a contemplative corner of memorial plaques and stones.

One interesting thing was a Wishing Ball. If you walked around this huge brass ball, your wishes would come true. Or so I hoped.

Unborn babies have a home at Ryozen Kannon under Kannon’s and a guardian deity’s auspices. It tugged at my heartstrings seeing the baby mementoes like baby boots, toys, sweets, and multicolored pinwheels, left for a child that never made it to enjoy these things.

Ryozen Gokoku or Gokoku Shrine looks bare for all the significance it holds as Japan’s official resting place for its war dead, on record, 73,011 of them. The lack of hoop-la, though, only draws attention to what lies there, inside, rather than to what is outside.

I walked uphill to the actual graves of the hero activists and patriots who fought and died to bring about the modernization of Japan.

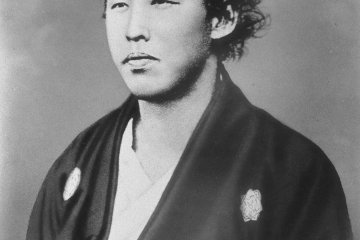

The leader was Sakamoto Ryoma. His grave is right on the top of the hill overlooking Kyoto. It may be modest, but still, this was a real man, not a myth or a God. Just the chap who turned Japan around to face modernization, so today I can jump for joy in the middle of jaw-dropping Kyoto Station. But maybe Sakamoto is turning in his grave.

His best friend Nakaoka Shintaro is buried next to him. They fought together till the death. They died young, assassinated at an inn at Omiya, Karamachi. I read it’s a sushi place today.

The tombs are edged along the hill, or in groves of stone plaques, tombstones, rocks, and cenotaphs. There is a lot of them.

The term gokoku is like a generic term for all such similar shrines. Kyoto Gokoku is in a good place, on a sacred mountain, Higashiyama. You know they are resting in peace.

The circle of Ryozens are about war and death, always a grave matter. Maybe this is why they were among the rare places in Kyoto that didn’t have 5,000 people standing around me, all very alive.

I thought I was on another planet. But the Ryozens are another planet.