What if you had a second chance?

It is better to be the head of the chicken than the tail of the bull. Watanabe san had always wanted to own a bookshop, even if it was the smallest one in Kanda. That dream was all-encompassing, occupying him day and night.

“What I treasured most was the stories of Sinbad, escaping shipwrecks and one-eyed monsters”, Watanabe confided. He loved adventure novels when he was young, stories of drama brought to life by his loving brother. As soon as he started working at the library, he squirrelled away his savings, but it was plundered by his uncle to repay gambling debts. When a pint-sized store became available, he burrowed to make his dream of opening the bookshop come true. The air raids over Tokyo in March 1945 destroyed his neighbourhood, his hand-picked novels reduced to ashes. With no way to repay his loan, he descended into a living hell. Torn between guilt and escape, he sobbed the day when he could not provide even a rice ball for his children. How he wished he had a second chance.

In the Nineteen fifties and sixties, Tokyo arose, like a phoenix from the ashes. With nothing left after the inferno, scrap metal from razed houses and oil cans from factory rubble were transformed into toy trains, cars, and automobiles, stamped “made in occupied Japan”. In a turning point reminiscent of a “swords to plowshares” moment, these tin toys exported to America paid for the lunches that saved Watanabe’s children. Some of these toys were a bit dented, with imperfections that only a mother could love. But flawed or otherwise, these were the toys that gave his children a second chance, and along with the rebuilding of society, led to Tokyo winning the bid for the Olympics in 1964. It was truly a moment of redemption for a country whose biggest cities were burnt to the ground, literally and metaphorically.

Imagine their tears of joy as they fulfilled their dream of seeing their children grow up in a safe and secure home, culminating in the Olympic Games. The candle of community that got them through the war, was still alight as communities got together to watch television. I recall the story of Yamamura san, so excited at the thought of watching the games that she asked all her neighbours, including the Watanabe family to join them. Tiptoeing over each other, they saw the country come together and finally put behind a painful past. It is hard to imagine how this was such a defining moment for Showa Japan, but it was a chance for the world to redeem itself, forget the pain of the past, and have hope for the future.

Likewise, the story of the Penny Candy Store Museum had rather humble beginnings, but at the same time, it is one about a boy who wanted to relive his past, not just for himself, but also for others in his and in future generations.

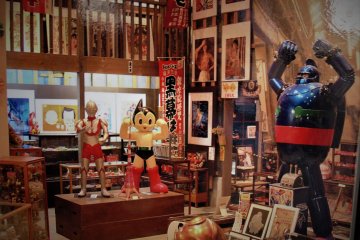

Hironobu Komiya didn’t have many toys when he was growing up, and the ones he did, were often found inside cereal and biscuit boxes. Even those toys were prone to disappearing, and so he caught the glimpse of some tin cars in a second-hand shop, it became the foundation of his 10,000-piece shrine to a golden era, one that is on display on what he calls Dagashiya-no-yume Hakubutsukan, or Dreams of the Penny Candy Store Owner Museum.

Certainly, there is an assortment of memorabilia on display, but the crowd favourites invariably involve entertainment of various genres, from tin trains to robots, or movie posters and old LP record labels. Invariably many toys are remembered from a male perspective, this is not to say that the curators were not being inclusive, perhaps more a reflection of those times.

It may also be said that in a digital world, people miss the tactile and three-dimensional appeal of tin toys and Godzilla-like dinosaurs from the Showa era. Just seeing them on display, even behind a glass display case, is enough to bring squeals of delight to young and old alike. Some of the toys can be touched and even played with as well, such as the old-school pinball parlour games that remain popular at many summer festivals today.

One of the joys of visiting this museum is seeing the neighbourly spirit it fosters amongst baby boomers who come here, with these tin toys reigniting memories, much like a school reunion. Of course, not everything was rosy, but time heals many wounds, and with the chance to reunite and reminisce, and to celebrate the spirit of community, survival, and wonder, is one that brings us closer together on a different level.