Gruu. Gruu. I heard that sound again. It started softly, then harder, then softer and harder again. Was it someone snoring? A bear? Now, buildings are not alive, right? Well at least I didn't think so, until I came here.

If plants and trees could breathe, then why can’t buildings which were built from the same soil and wood that nurtured the trees? It seemed that the architect had tried to recreate the idea of a living building, one that is in harmony with environment. You can't always hear it breathing. You have to shut everything out to notice it. Be still, close your ears. Maybe then you may feel it. This building actually supports a whole ecosystem. It has a hair of grass covering its head, which is neatly trimmed by the hairdresser, I mean gardener.

Designed by Terunobu Fujimori, La Collina was born on January 9th 2015 as a confectionery factory. La Collina means hill in Italian, giving a clue to the Architect’s intentions, with its hill like roof covered by a lush lawn. Surrounded by forested mountains, it is a stone’s throw from Lake Biwa, the largest lake in Japan. To Fujimori, nature and people are the protagonists of this building. Using materials from local forests, its assembly generated a community of human intellect and creativity. Fujimori was born in the Alpine forests of Nagano, and his childlike and non-judgmental way of weaving natural and human rather than machine elements can be seen in his portfolio. From the whimsical Takasugi-an, a tea room set inside a tree house, to the Lamune Onsen, playing on the bubble like qualities of a children’s fizzy drink, his works shifts your thinking about our relationship with the built environment.

“The Earth speaks to all of us, and if we listen, we can understand.” —Studio Ghibli’s Castle in the Sky (1986)

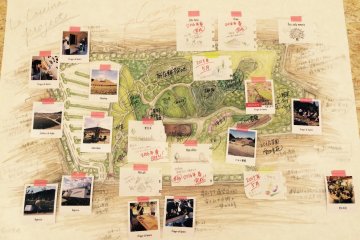

Like the grass above, this building is growing as well. By collaborating with local farmers, they have plans to open a produce market, as well as a bakery, a restaurant, and other sweets shops in the future.

On the first floor you can see them making Baumkuchen and Dorayaki first hand. Watching their intensity and the sense of spirituality in their craftsmanship, it is clear that they are not just making Japanese sweets and German cakes, but the manufacturing of memories.

The wood used in building this confectionery factory makes a cameo in the making of the sweets themselves. Come with me and look at the dozens of wood paddles on display. They look like some ancient artefact, but are actually used today, yesterday and many generations before as wagashi moulds, Japanese sweets that reflect the changing seasons and Japanese way of miniaturising nature, with sweets in the shape of cranes, rabbits and other natural elements. These wood blocks remind me of another Japanese icon; that of the woodblock print.

The Baumkuchen is made at Club Harie, which was founded in 1951 by Taneya , a wagashi maker. The owners were friends with William Merrell Vories (1880 - 1964), a Christian missionary and business man. Because of their friendship, they started to make western sweets, and kept true to their traditional recipe for more than 60 years.

They also make a Baumkuchen cake called baukemann. From the top it resembles a tree that has been cut across, revealing the rings that are markers to its time on earth. A symbol of life and longevity, the wedding ring shape of the Baumkuchen make it a popular bomboniere in Japan, symbolizing the bride and groom’s thankfulness for the opportunity to celebrate a new life together.

While you can buy Baumkuchen elsewhere in Japan, you can only learn about its history and experience the factory's co-operative culture here; which is all about loving and learning from nature, and connecting with people. Why not create your own memory with a gift from this store?