A gentle breeze sways the cotton Noren curtain of this café, telling visitors that it is open. A pink Frangipani and the blue skies bring a smile. A lounging cat and the trickle of water in the pond set the mood for relaxation on this cobblestone street filled with potters who have been hand-making kitchenware for centuries.

This is Uchina Bukubuku teahouse, a place of refreshment for sojourners from near and far.

History of Bukubuku Tea

In the sixteenth century, Bukubuku tea was served in the Ryukyu royal court to welcome envoys from neighboring kingdoms across the ocean. Its popularity grew during the Meiji period, particularly with weddings and the entertainment of guests.

Unfortunately, the Bukubuku tea utensils were destroyed in the Second World War. For Shota, it was painful enough to lose his family and friends, but the loss of the tea utensils meant part of his identity was lost until these utensils were found in Tokyo on the main island of Honshu.

It can be too painful to relive the horrors of war, but through the memories of celebrations, Bukubuku provided an opportunity for healing, a time of reconnecting with happier times, times that gave him identity and purpose. It is like the aromas of the tea bring back so strongly, these times that give him the opportunity to articulate the emotions behind his yearnings. It is these stories that are being revived in the Uchina Bukubuku Teahouse.

What was once limited to the royal court, can be experienced today at the Bukubuku teahouse, more than 500 years after its debut. It is amazing that you can still taste Bukubuku tea, made in the same century as when the War of the Roses, the printing press, and Machu Pichu were built.

Making of Bukubuku Tea

Bukubuku is essentially a roast rice tea, which Japanese cuisine connoisseurs may immediately trigger thoughts of Ochazuke, but instead is infused with the fragrance of Jasmine flowers. Unlike Ochazuke, it has notes of sweetness rather than savory or umami.

Jasmine tea was introduced to the Ryukyu kingdom during its trade with the port of Fuzhou during the Han Dynasty whose legacy is celebrated in the Ryukyu Lantern Festival. The jasmine flower used to scent the tea is venerated in Buddhist traditions, almost like incense. Jasmine tea grown in Okinawa is also called Sanpin-cha. Unlike Oolong tea, Sanpin-cha is only lightly fermented, giving it a subtle taste, more like green tea. To prepare Bukubuku, bancha or genmaicha can be added to the Jasmine tea. The aroma of firewood roasted rice tea adds another dimension to the scent of Jasmine flowers.

My first impression of Naha was the spectacle of colors from the coral reefs that greeted me as my flight descended over the harbor to the runway. The geology of southern Okinawa Island is rich with the limestone from the coral, and as the water percolates through these limestone deposits, it becomes hard, allowing tea makers to make lots of bubbles when frothing the tea. The rich minerals in the Okinawa soil make for a multi-layered taste in the black sugar, with a touch of salt, adding to the uniqueness of Bukubuku tea.

I was given an opportunity to make my own Bukubuku. Using a Chasen or tea whisk, I froth the tea until it foams with bubbles. These bubbles are set aside and added back it, making it look like a giant soft serve. Like a Cappuccino, the secret ingredient is the air, creating a texture that is surprisingly addictive. The frothing also brings out the aroma of the roasted rice and the jasmine. Actually, it is hard work frothing it for what seemed like ten minutes, so this is not a drink to be made in a hurry. Of course, you can just watch their artisans froth it for you but making your own Bukubuku is part of the experience here.

Bukubuku and Matcha

Bukubuku reminds me of a Matcha tea ceremony I attended in Kyoto, but there are a few differences that make it a unique Okinawan experience.

The purity and reverence in witnessing a matcha tea ceremony is truly a moment of meditation, which can be likened to the austerity of a Eucharist commemoration. It recalls the days when priests created tea rooms with doors that were so short that guests had to kneel to come in, to literally humble themselves when they enter this sacred space. Even the samurai had to leave their swords at the door.

Bukubuku on the other hand had a sense of theatre. The presentation of Bukubuku to visiting envoys was visual and textural, and even today, the tea bowl, foam, and whisk look oversized. Drinking Bukubuku can be challenging for beginners since the foam on top is huge and you need to first eat the foam with a spoon before you can drink the tea. The subtle fragrance of roasted rice and jasmine means you are not just eating air bubbles. With so much foam, it is easy to end up with bubbles on your nose, bringing laughter to the newly initiated class clown. The name itself is an onomatopoeia as if the sound of the bubbles is part of the fun, the essence of an Okinawan tea party.

The cloudy Bukubuku reminds me of Korean “rice milk” though neither is made with milk, despite its cloudiness, making it perfect for vegans. However, like milk tea or coffee, Bukubuku is often paired with sweets, such as shaved ice or Taimo Dengaku, literally field potatoes boiled with brown sugar syrup.

Philosophy of Uchina Bukubuku Teahouse

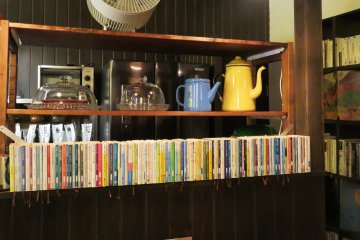

This is a perfect place to relax after a morning of sightseeing, and so it is only open between lunch and sunset. It is a place of Zen, after the energy of the morning is dissipated. Behind the tea house is a gallery featuring local folk art and crafts.

In the distance, you can see glimpses of the port, where ships take traders and passengers from distant islands. An ancient poet once said that "Buku Buku brings good luck on the day of departure. If you serve Buku Buku and send someone off, he or she will return to port safely." This is an auspicious drink with a promise of a future reunion.

Awamori or Bukubuku – the centrality of rice

There is a longstanding debate as to whether Awamori or Bukubuku should take the crown of Okinawa’s signature beverage. Alcohol or not, both drinks, along with Amazake and Sake, revolve around rice, which itself is revered in Japan. A drink made with rice may seem strange, but no one doubts the taste or the craftsmanship that goes into the making of sake or awamori.

Baisao, an 18th Century philosopher once said:

“Whether stranger or friend, knows my true mind. Sake fuels the vital spirits; works like courage, Tea works benevolently, purifying the soul. Courageous feats that put the world in your debt Couldn't match the benefit benevolence brings.”